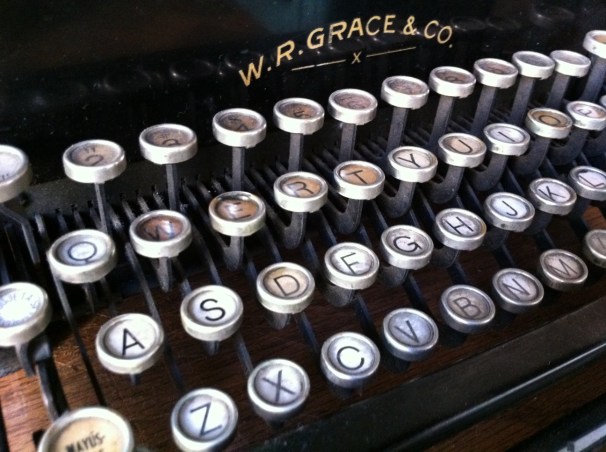

Letters like teeth: gaping, grinning, grinding, always pressing and impressing. It’s hard to hear beyond the chatter of the sentinel keys and the stories they speak. But sometimes there might be a cessation, a hungry sponging of the sound from a thing once submerged. The silence of an uncoiling truth. But who will listen to the dweller of the void?

I’m going to tell you a story. And like all good stories, this one starts with a lie.

In this telling, you will have to listen closely for what is not told. In a way, silence is the bedrock of every narrative—it is both its making and its unmaking. The empty canvas of a page wields the same power. With each word, another truth is imprisoned. As the blankness shrinks, a lie expands.

Once upon a time, the country of Burma sprung forth onto The Map. Not by a God, not by a myth, not by an indigenous people’s desire for nationhood on the page; but by British imperialism—which you could say—which they might say—acted as umbrella for ‘all the above.’ My telling of this is not the lie, the fact of Burma is the lie.

But let me make a few things clear. The Burmese people were not cropped from the creeping, inking, scraping, scattering fingers of the British Empire. No, they were there|here already. They had their own histories, their own space, and their own ways of understanding and cultivating both. But they were bled onto the page in neatly drawn lines that suddenly and unceremoniously grafted them into another narrative—the one we know, live, write within, and write upon—the Western narrative, our inescapable (sur)reality.

But Burma is as much a lie as it is a reclamation of a lie. After gaining independence, Burma, re-inscribed as Myanmar, had taken strides to reclaim its culture, legacy, and identity. No matter that in doing so they were filling up a void not their own—an imprint distinctly Western in shape and shadow. No matter that in filling this absence, Burma had merely repeated and refracted the lie of colonialism under a decades-long military dictatorship. No matter that in acquiring an identity, a nation-ness, so many existences were routinely excised. But what can be expected, when your country’s ‘origin’ is another country’s lie? You cannot blame the politics of Burma, as the tools used to shape their nation were the tools of their own oppressors.

The Burma ensconced on the maps is disembodied-in-embodiment. In other words, Burma’s lockstep with our narrative had been an untethering from its own. An Empire is just as much a sum of acquisitions as it is a sum of excisions. The (dis)claimed bodies are multifold—lands, humans, knowledges, histories, legacies—yet they all appear as one mirage, prophetically submissive to the confines of the page.

But who’s counting the excisions-by-acquisition? And if you are counted as excision, is your existence a void, a ‘minus sign’? Or, could the ‘minus sign’ be a hyphen, meaning: you belong in two stories at once? Can you belong in two stories at once? And, if so, would your belonging then also be an unbelonging?

Like every good story, this one is as concerned with providing answers as it is with finding them. Yet, the answers I seek are not in the ledgers of Empire. And even if I find them, they cannot be captured by my writing. Not exactly. The truths I seek are found in the open crevices between and around words, or acquisitions-in-writing. They are found in the diasporic blankness that fills the curves of each letter; look close and see a rigid elbow here, a sinewy hip there, the meander of whispers throughout.

One day, as the burden of Empire silently expanded across bodies and geographies, shaping family legacies of mirrors and masks, I came into the world, in a small town just outside of Philadelphia. But my mother was white. And in my middle-class suburban neighborhood, I felt like I was too.

It wasn’t until my grandfather passed away in 2008 that I became aware of a longing. It was like feeling the faraway ache of a limb you’ve never had—a limb that is still somewhere but not here. I had grown up hearing about stories of my family’s life under the British administration, the turmoil of WWII, and their eventual exile from Burma. It was when those voices began to fade that I realized, with desperation, not only what was lost but what could still be recovered—and that, possibly, a recovery could mean a re-making.

The story of Burma is about a loss. It is also a repetition of a lie. But in repeating the lie, perhaps space for new iterations of nationhood and legacy can be chiseled into—and out of—the map.

I hope you are okay with messes. I also hope you are not attached to beginnings or endings. You will have to get used to dislodging truth from un-inked spaces, even if it means rupturing the words on the page with the stories trapped in the whitewashed purgatory of its margins.

Recent Comments