I’ve argued that to be written onto a page is to be deprived of consent. Where your reality does not align with the content, you are rendered invisible. Where the words do speak for you, you are rendered voiceless. To have been embedded into the Western narrative, you are, in Franklin Henry Gidding’s phrase, giving “consent without consent”: “If in later years the colonized will see and admit that the disputed relation was for the higher interest, it may reasonably be held that authority has been imposed with the consent of the governed” (as cited by Chomsky 429). The civilizing mission of the West has largely ruled by acquiring “consent without consent” from subaltern bodies, spinning the end to the legacies of ‘Other’ cultures, as conferral of a new beginning. But once those subjugated (hi)stories have become embedded in the pages of another narrative, they are not able to recover and reinhabit their old story–they must disrupt the page from within, uttering discontent with unuttered ‘consent.’

This project has attempted to operate as a disruption of the page through complicating the notion of authorship: my story embeds multiple voices and therefore enables multiple authors. To author a reality–much like the task of the historian-in-conquering–is to invite complicity in its authorship. While the participation of the lives and experiences of those caught within the narrativizing are limited, the page also creates a space through which those disembodied stories might speak through, distort, and splinter into many the authoring of the origin narrative. In other words, while the “illusory coherence” of narrativity creates “a discourse that feigns to make the world speak for itself and speak itself as a story”, it also enables a discourse in which the story can speak itself as world–as multifold and constellated across time and space, involving the conflicting currents and tides of history and its human counterpart (White 2).

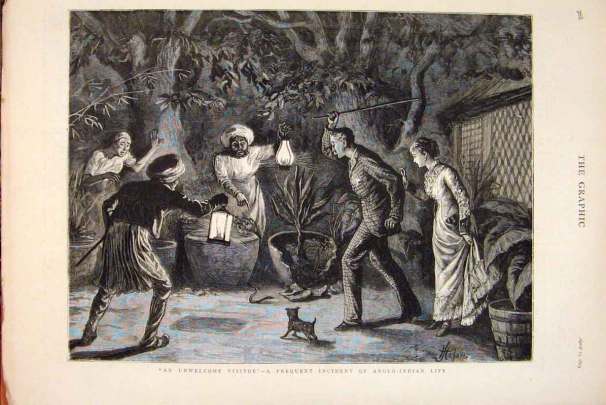

As much as I find endings false–adding to the lure of neatly linear narratives tied to painstakingly mapped spaces and scrupulously measured units of time–I wish to close this polyphonic narrative with a final image. In the following recollection, the counter-creep of the ‘second jungle’ works its ways from the underbelly of the Western narrative, forever encroaching on and destabilizing its perpetuated myths.

A snake sparks chaos as it creeps into the confines of a colonial estate. From “The Graphic”, a British news publication, 1879.

Picture this: it is late afternoon in Mandalay, Burma. You are in your home on a British estate–brick in the glow of sun-drenched green–where you have put in a long day making agricultural reports to be sent to the department head as recommendation. These reports will eventually dictate the content and quality of the goods produced in your country, their export value, and the profits of your boss’s empire. You approach your typewriter, fingers anticipating the familiar grooves and click of the keys. This typewriter is a symbol of your mastery of the English language, and the seat within its empire such mastery has awarded you—it is the reason you are able to keep servants and provide your family with opportunities the villagers and insurgents would never enjoy. You crack your knuckles and begin to type—but wait—something has caught the keys and interrupted your words. You push, and push, but the keys will not submit. With exasperation, you remove the parts of the typewriter, as you believe it must be an internal failure, that something might have slipped out of place. Suddenly you touch something foreign. It is a snake. You back away, leaving the typewriter agape like your countenance, and watch as a snake slowly uncoils itself from the insides of the machine, slithering towards the light of an open door, trekking back towards its home in the jungle.

This brush with wildness-in-civilization happened to my great-grandfather, Nunu’s father, during his days as head of the Department of Agriculture in the province of Burma. I find it to be a jarring reminder that the things colonization renders invisible—and that its colonized subjects might have submerged within themselves—does not simply dissipate, but it finds a home in the shadowed crooks of empire, nation, and selfhood. Though the colonizing hand might have cut back the jungle, its fierce creep grew beyond and around the scripts, biding its time till rediscovery or reemergence. I like to think of my hyphenated self—and the peri-colonial storyteller—as the snake within this typewriter. She has sort of but not quite found a home between the places where histories are submerged and new realities are grafted, the space between the keys and the worlds they wish to mold. As an academic, I feel sort of but not quite at home in front of the keyboard, yet I am always seeking the creeping thing that lies beyond the words on my page; and I am less trying to write it into being than to write for it a space to be.

Sun filters through the trees of my cousin Paul’s gently manicured garden, near “Zion Hill,” Burma.

On every page lies a story. Yet, every story does not have its own page. It is up to the hybrid or the peri, or those willing to navigate the diasporic margins of the page so that that its canvas might wield multiple stories at once. I have tried to accomplish this by embedding oral histories accompanying an academic narrative, within a mythology, as a beginning to experimenting with the limits and beyond-ness of the page—and by merit, the limits of the map, temporality, and legacy. Further, I have loosely charted my stories across four interlacing themes critical to composing and countering narratives and the potentialities they allow into shape: (Hi)stories, Content, Identity, and Form. Ultimately, I have attempted show how hyphens—the in-between spaces of ambivalence in empire—are not only a blueprint for decolonizing subjectivities, but also collective struggle:

“No one today is purely one thing . . . Survival in fact is about the connections between things; in Eliot’s phrase, reality cannot be deprived of the ‘other echoes [that] inhabit the garden.’ It is more rewarding—and more difficult—to think concretely and sympathetically, contrapuntally about others than only about ‘us.’”

(Said 336)

Just as the snake in the typewriter was a reminder to my great-grandfather of legacies submerged, and I, typing these words are an echoing of that reminder—speaking back both temporally and figuratively—the struggles of the colonized must act as reminders to one another of their shared origin: that of collective resistance and polymorphous re-utterance.

As Anzaldúa writes, “I see hybridization as metaphor, different species of ideas popping up here, popping up there, full of variations and seeming contradictions . . . the whole thing has had a mind of its own, escaping me and insisting on putting together the pieces of its own puzzle . . . It is a rebellious, willful entity, a precocious girl-child forced to grow up too quickly” (88). The hybrid is the peri of colonialism, forced into her role as victim and navigator of non-mapped spaces, creating new jigsawed landscapes within which conflicting narratives might embed—finding ways in which their grooves and outcroppings fit together or reshape one another. The peri creates a place in which fragments become synchronous and whole in their collective multiplicities. She knows that if we cannot fit into the ‘here’ of our history books, we must create an elsewhere. And the traces of that other place are found in the storied movements of snake under script, and bodies across diasporas.

Recent Comments